As a teacher in the US for almost 10 years now there have always been discussions swirling around about learned helplessness, whether we call it that or not. This discussion and burdensome attribute has not been a part of my experience observing students and classrooms in Finland, its absence is striking. I came here in part with an interest on how Finland engages its middle of the road students. What is important to understand is that their education system in many ways was designed from that middle. When Finland reformed its education system in the 70s and 80s the focus was on equity and access, not on achievement. Achievement happened as a by-product of a system that laid in supports to help all. As Finland’s international rankings have fallen there are very valid arguments that the system doesn’t push students to excellence and that it props up too many low achievers. Yes Finnish kids struggle, fail, are disengaged and don’t always value their education And no, they do not necessarily have greater ambitions or have a stronger work ethic than students in other countries. What they do have is unwavering autonomy. They own, their own education and that is powerful.

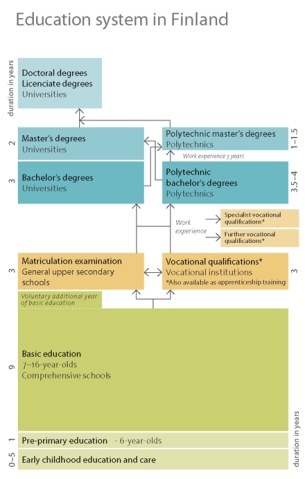

Päivä* sat with her classmates at lunch in the sun filled cafeteria of Stadin Ammattioppisto and after some prompting form her professor she started to open up about her path to vocational school. From a rural part of Western Finland, she attended a traditional lukio, upper secondary school. While many students (around 47% ) can and do opt for vocational schools instead of lukio after 9th grade, the course options are limited unless you want to travel or move to a major city at age 15 or 16. After graduation, when Päivä* didn’t get into the university program she was interested in on her first attempt, she decided to attend vocational school to pursue her interest in film & media production. This is a very typical reality for students interested in competitive fields of study and a very typically educational pathway forward. Päivä* didn’t see this “failure” to get in as major defeat rather as a redirection. There are so many different and continued paths at no or very low cost towards an education in Finland. Without a “point of no return” students stumble and change plans, all of and on their own ambition and interests. They fall forward. As a student in Finland you could enter vocational college in one of three ways, after completion of comprehensive education in 9th grade, after completion of lukio or at any time in your adult life. Depending on the school and program it is very typical to see 15 yearolds and 30 yearolds in the same program. Like in lukio, students are served free lunch and have access to social and health services. Additionally the comprehensive education courses prepare a student to choose either university or polytechnic higher education. The choice, the direction is theirs. A re-envisioned focus on flexibility is emerging in the comprehensive schools. I observed a 1st grade class that was in part combined with a kindergarten at Saunalahden koulu, in Espoo. These were students who needed a little more time with maturity and life skills education. The 1st grade curriculum was taught but adjusted to meet the needs of these students. The learning was much more interactive and chunked compared to other 1st grades I have observed. This day was an integrated math lesson about orienteering were the kids were using compasses to locate QR codes on the school campus to learn about architectural design elements of their school. This school, like many primary schools is in Finland, is starting to break the old system of looping where a student has the same teacher for 6 years of education, favoring more cooperative team or grade level instruction. It is not uncommon and there is no perceived stigma for a student to repeat 1st grade in favor of more time to develop skills or mature. Additionally while considerably less common, students may continue at lower secondary for an additional year after 9th grade if they need or want more time before making a decision about upper secondary schooling. If you are struggling with a math or any concept you can get special assistance regardless if you are deemed a special education student. Fluidity is allowed between grade and ability levels and this is increasing. How do they keep track of it all? I do not know and perhaps they don’t. Instead they focus on knowing their students very well and making the adjustments as needed. Teachers can do this because they also have and benefit from autonomy.  North of Helsinki in a lukio, I sat with 2 students who were working on some drawing assignments in the hallway. The one talked about choosing late morning classes in her first two years and how she is now paying for it with a jam packed schedule. (I wish I had learned this in high school instead of much later in college) Starting in 7th grade, using an online system students plan out their schedules. Teachers serve as group advisors and there are guidance counselors available to those in need. Graduation requirements are made clear but at what point/year a student takes a given class is very much of their own design- (ah hem… college readiness)

North of Helsinki in a lukio, I sat with 2 students who were working on some drawing assignments in the hallway. The one talked about choosing late morning classes in her first two years and how she is now paying for it with a jam packed schedule. (I wish I had learned this in high school instead of much later in college) Starting in 7th grade, using an online system students plan out their schedules. Teachers serve as group advisors and there are guidance counselors available to those in need. Graduation requirements are made clear but at what point/year a student takes a given class is very much of their own design- (ah hem… college readiness)

This structural autonomy goes well beyond flexible class schedules, frequent breaks and alternative working spaces. It starts very young. From a US perspective autonomy seems to be something reserved for older students or at least we criticize its lack in older students. Much of the work completed in and out of class by Finnish students is not graded. Grades do not drive student achievement. In talking about this with teachers, it is because the class activities are considered practice and informal assessments. They want to encourage students to study for their own learning and take risks. When I ask students about this they say more grades would just make it more stressful, not more valuable. I really like this way of thinking but it relies on students having a strong intrinsic desire to learn. Just why do these students do the work? Samu* an 11th grader in the English class I have been working with had this to say about students’ drive to be educated; “We start out with a lot of trust from our parents and expectation too, we get ourselves to and from school starting in 1st grade. By 7th grade you are really on your own making your own decisions about how you are going to manage school, you pick your own classes and you are free to mess it up- but it’s your mess-up…You always know that. It’s my education, it’s my time I need to be the control of it. If you don’t do the work you quickly realize you won’t understand or pass the course, no one is going to learn it for you and you can’t just keep repeating. By the time you are in lukio or whatever you are doing you want to get on with your life, you want out from under your parent’s home. You realize you have to get serious to get through school. There is a lot of stigma if you are 20 years old and still living at home. You are 18, you graduate, you start your life. You just can’t do that without an education.” It seems these reciprocal levels of autonomy, trust and expectation between students, teachers and society are the antidote to learned helplessness. I’m wondering now what can I change about the way I structure my teaching to help my students back home fall forward more often? *Students names have been changed

70’s in US community colleges saw a similar tact – less required courses, more elective choices, pass- fail, non punitative grading (A b c d courses and objectives to be completed) and optional attendance. But it gave way to champions of the big red F. Dad

LikeLike

… as a somewhat non-traditional student – I have always found the European education system somewhat clinical. Even with this perceived freedom of choice it narrows the options for underperforming students who may not be ready to chose direction regarding college and their future at 13 years old. I suppose I am more interested to learn how Finland addresses skillset gaps that emerge over a workers lifetime. Have you been exposed to any adult learning processes while ‘in country’ that address this concern?

LikeLike

While I haven’t been looking specifically at adult education it often overlaps in scenarios like the vocational colleges. While many programs are a mix of students in and post upper secondary schooling there are many institutions that are exclusively for adult learners. With education being free through the masters level, fees are typically minimal. There is a strong tradition of adult education in Finland. Why I think it has been successful is that the entire education system is integrated , meaning that the design thinking that is considered in the development of the comprehensive schools is also applied to higher and continuing education. Professional development and educational choice are seen as part of the work experience, not just given lip service. Many of the people in our building are in Helsinki for professional development experiences that they have both sought out and are part of their work life. The availability of retraining and/or vocational programs is very tied and scaled to the economic needs and ambitions of the country. Responsibly linking to the workforce however potentially limiting to personal interest.

LikeLike